Adapted from remarks delivered by Vince Warren upon accepting the 2016 Haywood Burns Memorial Award for Lifetime Achievement from the Civil Rights Committee of the New York State Bar Association, New York City, January 28, 2016

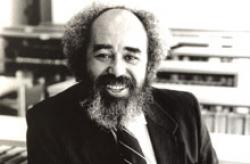

Haywood Burns

Haywood Burns is a legend in the struggle for social justice and civil rights. He was someone that I looked up to, admired, and wanted very much to be like. He got his start in social justice work not as a lawyer, but as a teenager who successfully helped desegregate a swimming pool in Peekskill, NY, his home town. He participated in Freedom Summer, going down to Mississippi in 1964 to register voters. In 1969, he helped found the National Conference of Black Lawyers, an organization that would come to mean a lot to me in my career as a lawyer. He ran for the Harvard University Board of Overseers on a divestment from South Africa platform. And he, like me, was a trustee of the Center for Constitutional Rights, the organization I now run. Like Haywood, my path didn't start in law school. It started when I was 19 years old at Haverford College, where I was one of the leaders of the campaign to divest from companies doing business in South Africa as part of the international boycott of Apartheid and the economic and political forces that supported it. It was this work that led me, upon returning to New York, to connect with lawyers and activists, including Haywood, at the National Lawyers Guild and the National Conference of Black Lawyers and work as a paralegal on police misconduct cases.

After a few years, I found my way to the counsel table in the Central Park Jogger criminal trial as a paralegal on the team that was representing Yusef Salaam, who, years later, like his co-defendants (the Central Park Five), was exonerated after being convicted and spending years in prison. I was outraged by the criminal trial process. It was clear to anyone who took a close look at the facts that these young boys had confessed to something they didn’t do. But no one cared, least of all the prosecutors, and no one would even listen. Who they – and likely members of the jury - were listening to was Donald Trump. He took out full-page ads in four New York newspapers that referred to “roving bands of wild criminals” and called for the reinstatement of the death penalty.

I knew I wanted to be a lawyer after that experience, but I needed some guidance to make sense of it all and of how I might make a difference. So I called Haywood for advice. Haywood and I met on a brisk, cloudy day in 1990 at CUNY law school. He told me, with that broad smile and those wonderful shining eyes of his, that in this line of work, the only thing that would limit me would be my discomfort with demanding from power what needed to be demanded and saying to power what needed to be said. I didn't fully appreciate how complex this challenge would be until years later, but it opened me up to possibilities in the law that I never knew existed. I was on my way.

When Haywood died in 1996, killed in a car accident in Cape Town while attending a human rights conference (along with Shanara Gilbert another dear friend and mentor of mine), he was only 55. I'm now 51. In thinking about what it means for me to be honored with this award named after Haywood, I am reminded of what I learned from this incredible human being. I learned that the time to act against injustice is always now. I learned that every day counts. I learned that we cannot wait to take on the massive, intractable issues that affect those who are most vulnerable, issues like stop and frisk, solitary confinement, and race-based police killings, because the millions of people who are subject to this violence cannot afford to wait .I learned that to do this work with integrity – demanding what needs to be demanded and saying what needs to be said – you must embrace it as your life.

So much of the work that I'm most proud of, the work that motivates me to recommit everyday, is the work I do with my colleagues at the Center for Constitutional Rights. Many of you know CCR as the legal organization that in just the last few years won the stop-and-frisk case in NYC; ended long-term solitary confinement in California; obtained the first award for plaintiffs tortured in the wake of 9/11; obtained a searing Third Circuit indictment of the NYPD program spying on Muslims in New Jersey; established the first precedent in U.S. courts for persecution of LGBTI people in Uganda as a human rights violation; and represented students throughout the country to protect their First Amendment rights to support Palestinian human rights.

But many of you may not know that CCR has been taking on cutting edge issues like these for 50 years. This year, 2016, marks our 50th anniversary as a force for radical justice through the law. Very few things that constantly push the envelope, seek to disrupt what people are comfortable with, or seek to dismantle structures that undergird everything that is wrong with the world last for 50 days, much less 50 years. But we do what we do – and I do what I do – because the times still require it.

As I hear much of our country pondering whether we're in a post-racial America, I recall what Haywood once said about this question: "[a] race-transcendent politics is most likely to succeed when the white community takes responsibility for overcoming its racism, not when the black community decides to forget it." We know we have no intention of forgetting it. The Black Lives Matter movement has newly emerged as a movement that finds itself uninhibited by shyness, politeness, and the civility of a status quo. Those folks would make Haywood proud. It would also make him proud to know that the Center for Constitutional Rights, responding to the times as we always have, launched #Law4BlackLives a massive cohort of about 1000 lawyers who have come together - much like I came to Haywood two decades ago -- knowing that it is their duty to lend their skills to our unfinished civil rights movement.