In August, I was down at Guantánamo to represent Mohammed Kamin, an Afghan detainee who has been held at the prison for almost eleven years. (I left a six-month-old baby boy at home to travel to Gitmo; so, in a way, did Kamin: his son was that old when Mohammed was first detained, and is now thirteen.) The occasion was Kamin’s hearing before a military “Periodic Review Board” (PRB) that was charged with the task of deciding, after just a few short hours spent questioning and talking to him, whether our client can be safely released and sent home.

Luckily the Board has more than just the live hearing to guide its decision. There is a small stack of paperwork summarizing the government’s intelligence about Mr. Kamin’s past, and an enormous volume of letters asking that he be sent home—from family, local officials, Afghan national politicians and all four of the military officers who worked over the years on the defense of his military commission case (which the prosecutors dropped long ago).

Why is a guy like this—said even by the military to be nothing more than a small-fry insurgent, a “foot soldier in a war he did not understand”—still in detention at all? The military officers who wrote in support of his release all served in places where our armed forces fought against a local insurgency; none of them are naïve to the challenges of quashing one. As one of them noted in his letter, if Kamin had been detained as part of the insurgency in Iraq, even assuming the government’s accusations against him were true, he would have been processed through the domestic system and released in a few months. If he had been kept in Afghanistan where he was initially detained in 2003 and spent a year held by our military, he would surely have been processed through Afghanistan’s national Peace and Reconciliation Commission system and been sent home long ago.

But he wasn’t kept in Afghanistan. During that first year in military custody, the Supreme Court decided (in a case called Rasul v. Bush) that Guantánamo detainees had the right to challenge the legality of their detention in federal court. After that decision, there was no reason for the Bush administration to bring any overseas detainees to Gitmo. Yet Kamin and seven other prisoners were sent from Afghanistan (where they then had no right to challenge their detention) to Guantánamo in September 2004 – three months after Rasul. The only reason bringing Kamin halfway across the world makes any sense to me (rather than keeping him in Afghanistan) was to provide fodder for the struggling military commissions system – a simple case, uncomplicated by waterboarding.

Eventually, when President Obama’s interagency Task Force re-reviewed all the cases in 2009, it decided Kamin should not be prosecuted (even though the government then believed it could lawfully charge “material support” and “conspiracy” as war crimes in military commissions). Again, I think the best explanation is that Kamin probably never should have been brought this far away from home to begin with. Only the politics of the commission system in 2004 likely brought him here, and eventually the intelligence bureaucrats on the Task Force, looking at the case objectively, decided that it didn’t make sense to charge him. Although he is no longer actually charged, nor recommended for charge, nor chargeable in theory (the courts have since held that his supposed offenses weren’t war crimes), Kamin remains, because of his fateful transfer to Guantánamo, one of the last victims of Guantánamo’s failed military commission system. He also remains one of the last Afghans held in the prison.

* * *

Prison usually damages people; most of our clients leave not angry but rather broken and depressed. But there are also quite often people who become philosophical about their imprisonment and actually take something valuable away from the experience; they learn to appreciate life better for the experience of incarceration. Kamin is one. He has expressed gratitude for being taken off a self-destructive path by his arrest. For someone whose worldview was very narrow, formed in the Afghan countryside, Guantánamo has in his words “been like high school”—as terrible as it is to be in prison, it also opened a window onto a larger world that he was utterly ignorant of before he was arrested. He’d never even seen a TV before he got to Gitmo. When he leaves, he’ll leave a different person. As the military officers’ letters repeat over and over, he is not bitter about his years of detention, not angry at the United States, and wants nothing more than to return to life with his wife, child, and larger family in Khowst.

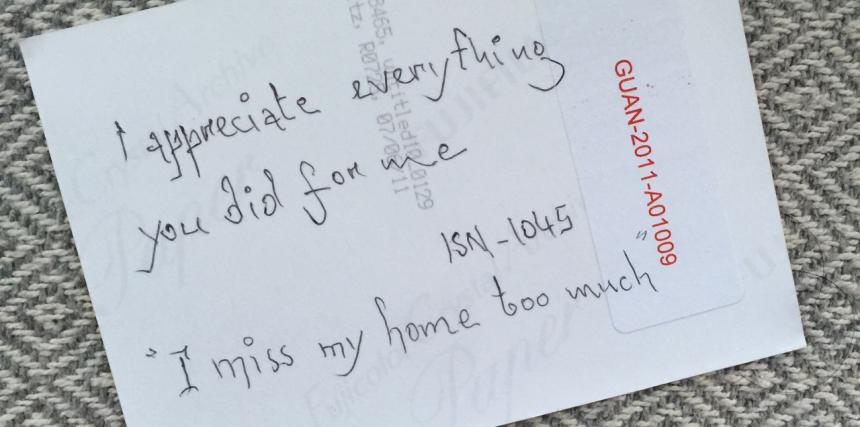

The Board deliberates right after the hearing session, which was held on August 18th, and under the standard schedule we will probably learn of its decision sometime in late September. Meanwhile, Kamin left us with a memento: a small handmade card that reads, in English, “I appreciate everything you did for me.” It is signed “ISN-1045,” and the use of his prison number rather than his name made me realize the note might anticipate either success or defeat and continued detention. Underneath that is a final line that might explain why Kamin would deny himself too much optimism: “I miss my home too much.”